It would be a brave person to say that they think they know what the 2014 election will deliver. Apparently, Claire Robinson is very, very brave.

Claire Robinson has a piece in the NZ Herald about the 2014 election that I have some problems with. It's not so much her claim that National will lead the government after the next election that bugs me; I'll accept there's at least a 50-50 chance that this will be the case.

No, it's the attempt to portray this claim as somehow inevitable or destined, based on the things that we know at the moment, that I take issue with. So I'm going to give it the full cut-paste-and-comment treatment. Here goes.

If recent history is anything to go by, the 2014 general election result has already been decided. As the chart to the right shows, since 1998 the party leading the opinion polls in July of the year preceding the election has gone on to win the highest proportion of the party vote, enabling them to form a government.

OK - this is going to be banging my head against a brick wall, given how often I have written on the issue before. But - and here come the bolded italics - under MMP, winning the highest proportion of the party vote does not necessarily enable you to form a government!

It is true that so far under MMP, the highest polling party has then been able to gain sufficient additional support from others to form a government. But to turn this pattern into some sort of iron rule of government (as Claire at least appears to do here) is both constitutionally dubious and likely empirically false. At its worst, it leads to the sort of silliness exhibited in this NZ Herald editorial, which argued that even if Labour and the Greens had enough seats in Parliament between them to govern, they still ought not to form a government if National got the most party votes.

So, while I very much doubt you'll find anyone outside of the most optimistic and borderline delusional Labour Party supporters who believe National won't be the largest party in Parliament after the 2014 election, that isn't really the important question. Rather, it is how big will National's share of the party vote be, and (just as importantly), will it have sufficient support partners to give it the extra votes in Parliament needed to govern?

And, with respect, thinking you can answer either of these questions with any degree of certainty a year out from the election is somewhat wishful.

I get that perhaps all Claire means is that in the elections we've had so far under MMP:

(1) The party with the lead in the opinion polls 12 months out from an election goes on to become the largest party after the next election; and,

(2) The largest party has then led the government.

What that requires us to remember, however, is that the data-set establishing this "pattern" consists of only six examples. So to extrapolate from it in order to claim with any sort of certainty that this election will be the same as the past ones, despite the very different level of support for the various parties and the different confounding variables (such as who may win what electorate seats), is dangerous in the extreme.

Despite the current centre-left Labour/Greens bloc looking competitive, history tells us National should have the 2014 election in the bag, again.

How is this possible when there is a lot of water to go under the bridge between now and the next election? The Labour Party has only just got a new leader and not a single cent of money has been spent on campaign material and advertisements by any political party. Surely voters will be waiting to see what tricks David Cunliffe can pull out of Labour's hat before coming to a decision?

Well, it's counter-intuitive, but election campaigns in New Zealand don't actually make much difference to the outcome of elections for major parties (although they do for minor parties).

Data gathered from the New Zealand Election Study since 1999 shows that on average almost 54 per cent of voters will make their decision about which party to vote for before the election campaign. While pre-existing party loyalty is a significant factor in the voting choice of these 'early deciders', international research shows that they also base their decision on performance measures they already know or estimate well out from the election campaign.

Some 62.7 per cent of National voters make their voting decisions before the election campaign; 40.4 per cent of them make that decision before election year. It is these voters Labour needs to reach across to if it is to have any chance of regaining the box seat - but most of them have already made up their mind, and it will take a miracle to convert them.

I can accept these figures, without buying the blanket claim that campaigns "don't make that much difference to the outcome of elections for major parties". Take 2002, say, and what happened to National's share of the vote as the campaign proper proceeded. Or, indeed, what happened to Labour's share of the vote as "corngate" unravelled in the last few days of that campaign. Or what the Exclusive Brethren saga meant for Don Brash's chances of tipping Helen Clark out in 2005. Or what "teapotgate" may have done to John Key's quest for an outright majority in 2011.

Sure, these examples may have involved only a 1 or 2 percent change in the party fortunes of Labour or National (although in the case of National in 2002, it was far more than that). However, it's these margins that can separate winning from losing (see Brash v Clark in 2005), or from winning an absolute majority (as Key found in 2011).

But let's put history to one side and simply consider the figures Claire herself gives. Let's accept the NZES data that 40.4% of National voters decide they will vote National a year out from the election (which is where we are now, the point in time at which Claire is declaring that "recent history tells us" the election is all but over). That then means that 59.6% of them haven't made that commitment. Now, we have no idea what exact share of the party vote National will get in 2014 (that's why we have elections) ... but let's randomly stipulate that it will be equal to the 45% it got in 2011. That means some 26.6% of the total votes we may call "National's" are still in play right now, a year out from the election.

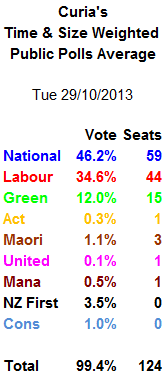

Then consider David Farrar's most recent synthesis of polling data:

(Or, if you prefer your reality with a more left-wing shading, consider Danyl Mclauchlan's "corrected" poll-of-polls).

This is edge of the knife stuff. A percent shift one way or the other (or, just as importantly, an electorate voting one way of the other ... how confident is anyone with David Farrar giving Act or United Future a seat?) and you end up with radically different government options. So to say with any sort of confidence that, on the basis of those voters who have committed their support here and now, "the 2014 general election result has already been decided" seems somewhat hubristic.

David Cunliffe will need to convince National voters that his recent rekindling of Labour's relationship with the union movement is also in their interests. It may have worked to shore up Cunliffe's leadership ambitions, but persuading more conservative centre-right voters to swing to the left will not be such an easy ask.

Without being able to rely on these voters, Cunliffe will have to share the spotlight with the Greens' Russel Norman and Metiria Turei in order to present a viable leadership alternative to the National-led government. This isn't necessarily an easy coalition. The closer they get toLabour, the Greens risk becoming regarded as 'Labour-lite'. If they are to grow their support base they need to keep taking voters off Labour and presenting themselves as significantly different from Labour.

Conversely for Labour to grow they need to take votes off the Greens, which means that they can't become too chummy either. It won't be easy for either party to present itself as a shared and unified offering when deep down they are competing for the same votes.

Sure, if that is Labour's strategy, it's going to be a tough one. But, as Danyl Mclauchlan (him again!) points out, 26% of enrolled voters didn't cast a vote in 2011. So the 2014 election doesn't have to be a zero-sum game, in which parties are restricted to taking votes away from competitors.

Now, maybe Claire would argue that the difficulty of reengaging these non-voters dooms any strategy based on doing so to failure. Or maybe Claire would point to long term voting trends to say that parties inevitably have to restrict themselves to fishing for votes in an ever-shriking pool. I don't know.

I suspect, however, that Labour will run a dual-pronged strategy - the approach that National and its communications team are trying to label "yeah-nah". It'll try and pry off some votes from National, as that party continues to get shop-worn from the realities of governing. And it'll try reenergising its base, to make voters believe that 2014 is winnable (and worth winning) - because close and "important" elections generate more turnout. Whether it can make this work, I guess we'll see. But offers something different to the crude duality that Claire describes.

Although David Cunliffe emerged from the Labour leadership 'primary' with all guns blazing, recent political history also suggests he will find it hard to make a sustained impact within the next 12 months. The MMP era is littered with major party leaders who have rolled their predecessors with the hope of doing better within two to three years of the next election, only to fall by the way.

John Key was the exception as leader of the Opposition for just under two years before he became Prime Minister; before that Helen Clark was leader of the Opposition for six years, and before that Jim Bolger was leader of the Opposition for 4.5 years. No one has yet gone on to lead a government within 12 months of assuming party leadership.

So ... before John Key did it, no leader of the Opposition became Prime Minister within 2 years of taking over the role. But now, because no leader of the Opposition has become Prime Minister within 12 months of taking over the role (actually, David Cunliffe will have been leader of the Opposition for 13.5 months by next November's election, but no matter), David Cunliffe won't be our next Prime Minister.

This cartoon answers that faulty piece of reasoning.

Of course none of this means that forming the next government will be easy for National. Its current support parties in government - ACT, United Future and the M?ori Party - have all suffered serious reputational damage and declining popularity over this term of government, and their continued ability to survive the next election, let alone collectively prop up a National-led coalition, is not guaranteed.

And now we're getting to the nub of things. Because unless Claire thinks National is going to win an outright majority - which she can't, because (i) this has never happened before under MMP; and (ii) no governing party under MMP has seen its share of the party vote increase in its second election as government - then she has to find support partners for it to govern. Which is - as she herself notes - very difficult to predict in advance because "election campaigns in New Zealand don't actually make much difference to the outcome of elections for major parties (although they do for minor parties)." So to say with any degree of certainty that National will lead the next government, Claire has to know a full year out what will happen during the 2014 campaign (which, as she herself admits, can make a real difference for the minor parties).

Of the three minor coalition partners, the Maori Party is the most likely to survive through the 2014 election. David Cunliffe has too much on his plate over the next 12 months to be able to reassure voters in all the Maori seats that he is in a position to prioritise their interests. So there will still be room on the political spectrum for a party or parties dedicated to Maori needs. With a new leader in Te Ururoa Flavell, we are likely to see a reinvigorated Maori Party, but it's not looking likely that Maori and Mana parties will be able to reconcile over the next 12 months in order to win all the Maori seats.

This is true. But why assume that the Maori Party will be a support option for National, especially if they are the only support option available? The argument "but they've supported National for the past two terms" ignores a critical point - National could have governed without them, anyway. In other words, supporting National was a step the Party leadership could sell to its members on the basis that there's nothing the Party could do to stop National governing, so why not get some benefits out of the inevitable?

Put the Maori Party in the balance of power, however, and that picture changes markedly. Could a Te Ururoa Flavell-led party sell to its members the idea of allowing National to govern, where there is some sort of governing alternative available? And if there is no governing alternative available (as was the case in 2008 and 2011), then that means National can majority support without the Maori Party. Meaning that either the past behaviour of the Maori Party is no good predictor of its future actions (because circumstances have changed), or the circumstances are the same as the past and the decision of the Maori Party won't affect who gets to govern.

As always in New Zealand politics, the wildcard is New Zealand First. Assuming that Winston Peters wants to take another crack at electoral politics (and there are no signs that he would not) it should be expected that New Zealand First will wait until the election results are known before committing to any arrangement. Assuming that the party gets over the 5 per cent threshold, its main options would then be to go into coalition with National, go into coalition with Labour and the Greens, or remain on the cross benches and vote issue by issue.

With a party membership that has previously indicated a preference not to be in formal coalition with National, and faced with the alternative prospect of being the third (and least important) party in a Labour/Greens coalition, the most likely scenario is that New Zealand First will choose to stay on the cross-benches, supporting a minority National Government on confidence and supply, much as it did for the 2005-2008 Labour-led government.

In this scenario it would be in the powerful position of having the casting vote on every piece of legislation before the House, with management of a Cabinet portfolio or two thrown in for good measure.

In other words, NZ First may do the deal with National that it did with Labour in 2005 -11. The constitutional lawyer in me grits his teeth a bit at this arrangement being described as "sitting on the cross benches", as such enhanced agreements for confidence and supply have become the "new normal" for governing arrangements. We should call them what they are: co-governance agreements. Such pedantry aside, however, it is perfectly true that Peters could do what Claire describes.

The chances of this arrangement occuring are then something that different observers will have different views on. However, I'd suggest that insofar as National's path back to power depends on it happening, it's far short of being a "decided result".

But there is an even wilder card that may yet disrupt this scenario: the Conservative Party. In the 2011 election it got 2.65 per cent of the party vote, which is more than any of National's coalition partners.

Off the back of population increases it is possible that a new electorate may be formed north of Auckland, currently a National-leaning geopolitical zone. It would not be without precedent for National to 'gift' the winning of that electorate to party leader Colin Craig to ensure that the Conservatives' party vote may be counted in a new centre-right coalition bloc. National might then be able to govern without the need for the support of New Zealand First. Either way, it has options.

This is true. As Tim Watkin posted here, the Conservatives have the potential to change the electoral landscape considerably. But they also have the potential to implode and drag National down with them. In 2011, Craig flew under the radar for the most part. In 2014, he's going to be in the spotlight. As will the various people who get chosen to stand in the party name. Do we have any idea how that is going to work out, especially if National is forced to clasp the party close to its chest by trying to gift Craig a constituency seat?

Furthermore, there's the very problem that Claire pointed out with regards Labour growing its vote. To what extent will the Conservatives succeed in simply pulling support off National, as opposed to growing the centre-right bloc vote by taking votes from Labour and NZ First? Could it even do a NZ First in 2008, and fail to make the representational threshold, thereby consigning some 3 or 4 percent of the centre right's vote to the dustbin?

The fact that these are all questions we don't yet know the answer to - and these are only the "known unknowns", without considering the "unknown unkowns" out there - indicates how much of an open ballgame the 2014 election is. Claire may very well be right, and history will repeat. But I'd say it is equally likely (or unlikely) that Claire will be proven wrong, and that something else will happen.